Dunbar’s Problem: morality, fitness, and peace

Projects | | Links: GitHub | Read More

If morality is a proxy for fitness what morality maximizes peace? IMAGE SOURCE

If morality is a proxy for fitness, what kind of morality would maximize peace?

To explore this question, we study games—not for entertainment, but as models of human interaction. Game theory allows us to test which sets of moral rules promote cooperation, reduce conflict, and ultimately enhance collective survival.

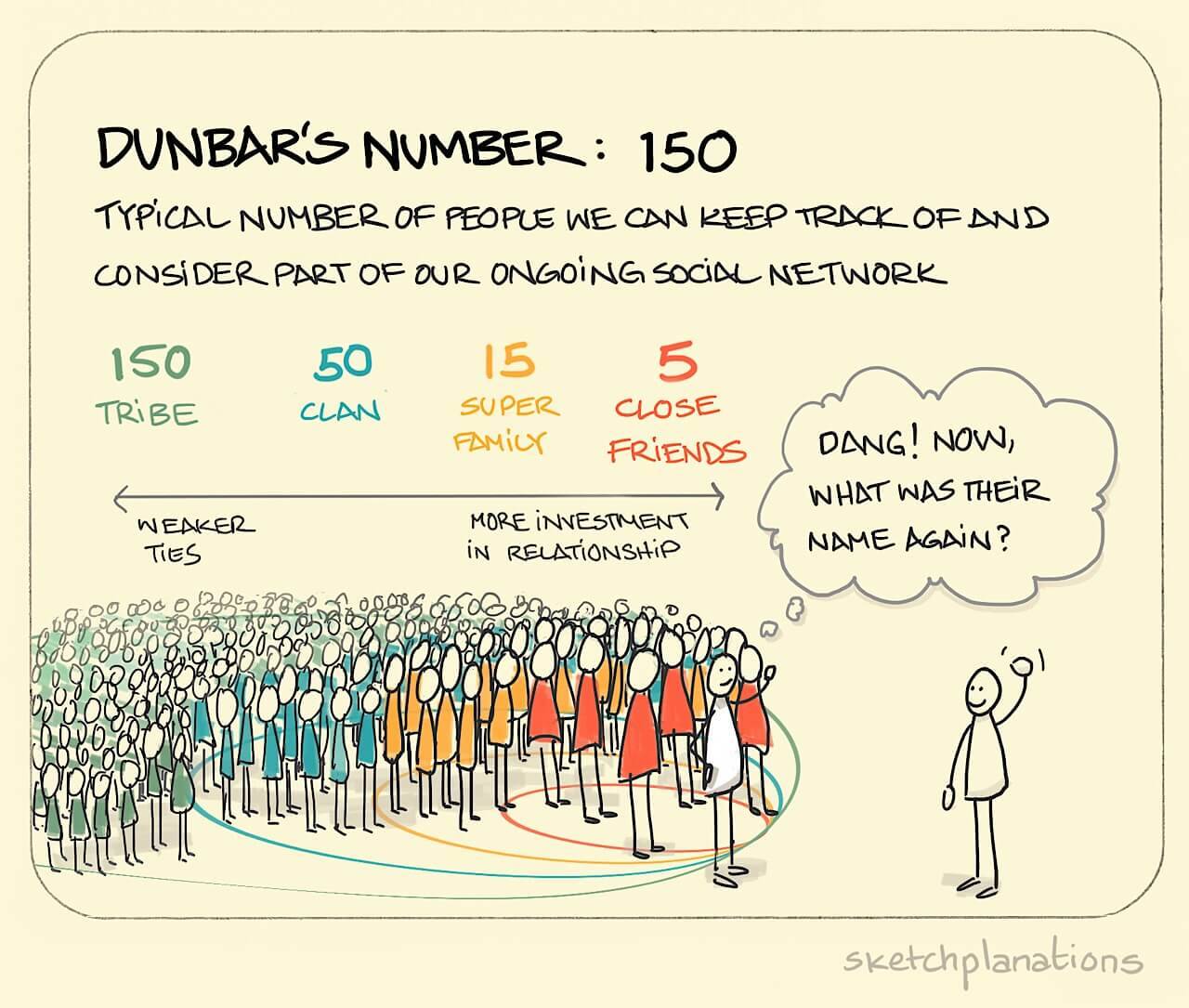

This discussion ties closely to Dunbar’s Number: the cognitive limit (around 150) on the number of stable, trusting relationships a human can maintain. Historically, when tribes grew beyond this number, they split into smaller groups. Each split brought new competition for resources, often leading to conflict.

A simple but famous example of this kind of dynamic can be seen in the Karate Club network study by Wayne Zachary (1977).

Zachary observed the social ties within a college karate club, mapping them as a network. When a disagreement arose between the instructor and the administrator, the network fractured into two groups—not randomly, but along the fault lines of social relationships. In network science, this case study has become a classic example of how social cohesion and group alignment predict splits.

Now scale this up to today:

With a global population exceeding 7 billion, humanity effectively forms ~45 million “tribes” competing for the same finite resources. This creates unprecedented tension and instability.

If we view morality as an adaptive tool—a set of behavioral rules shaped by evolution—then the challenge becomes clear:

How do we design (or evolve) a morality that maximizes not only individual or tribal fitness but humanity’s fitness as a whole?

This is the core of our work: using models and simulations to explore which moral frameworks promote peace at a global scale.